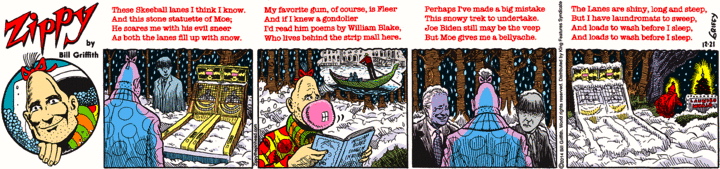

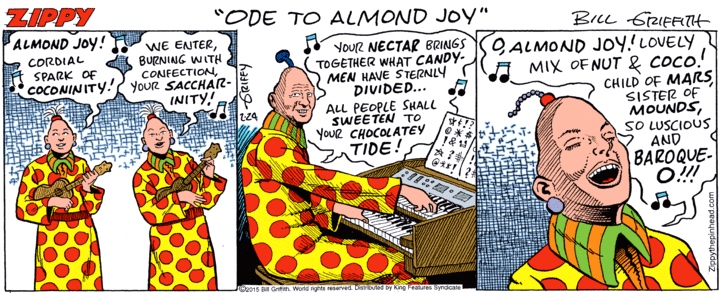

That, at least, is where it started, with this bit of playfulness on Facebook:

![]() (#1)

(#1)

One among a great many available versions of Wading for Godot (like this one, hardly any have an identifiable origin, but just get passed around on the web, along with jokes, funny pictures, and the like: the folk culture of the net). I’m particularly taken with #1, as a well-made image and as a close reworking of lines from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot:

Vladimir: Well? Shall we go?

Estragon: Yes, let’s go.

(They do not move.)

The Big Picture. The name of the play has three words in it, and each has served as the basis for playful variations; such variations are common for well-known titles (and other formulaic expressions — a few go on to become snowclones, but most are one-offs and do not).

That’s playing with the title of the play. But there’s also playing with the work as a whole: mimicking the setting, characters, story, and even the text in detail. This posting will end with a magnificent parody of this sort, in which Waiting for Godot is realized as a comic strip featuring (the simulacra of) the animated-sitcom characters Beavis and Butt-Head.

Title play: word 1. As above, with the pun waiting / wading. The two words are phonetically similar for all speakers of English, but for most American speakers, the words are phonetically identical, or at least close enough to strike people’s perceptions as identical (the actual phonetics are more complex, and often involve small but statistically significant differences in pronunciation).

The phenomenon of AmE at issue here is the “flapping” of the alveolar consonants t and d — realizing both as a voiced alveolar tap or “flap” [ɾ] between an accented vowel and an unaccented one (as in atom / Adam, patty / paddy, rater / raider, etc.).

Otherwise, you can find apparent examples of

Waking / Wailing / Mating / Waving / Wasting for Godot

but so far they’ve all turned out to be errors in character recognition software that generates text or in software that searches text (or both).

I would love to see Waltzing for Godot developed, but would prefer to avoid Maiming for Godot.

Title play: word 2. At least one instance, the title of an academic paper:

Paul E. Corcoran, Historical endings: Waiting with Godot. History of European Ideas 11.331-49 (1989).

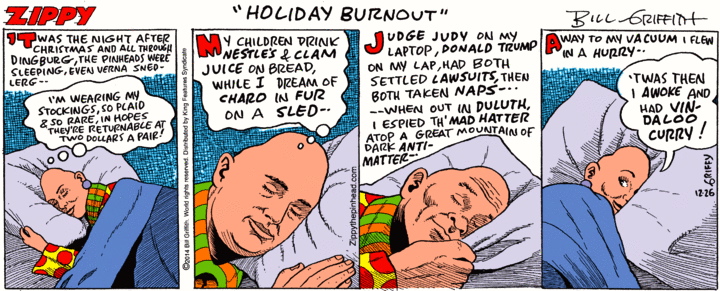

Title play: word 3. From my 10/14/16 posting “Pun days”, image #2, a cartoon by Walsh:

![]()

(#2) Involving the Waldot of Where’s Waldo

This posting also has a section on Beckett’s play, on Vladimir and Estragon and the landscape they find themselves in, including that tree.

Much more slyly, from a Slate piece by Alex Ross on 9/10/96, “Island of Lost Auteurs: What the hell happened to John Frankenheimer?”, about director Frankheimer’s The Island of Dr. Moreau, “a succès de désastre starring Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer”. Ross’s piece is perceptive and wickedly, achingly, funny; then in the middle of it:

Waiting for Moreau, I’ve been captivated by three of Frankenheimer’s movies with his favorite actor, Burt Lancaster.

My own take, in my 3/21/12 posting “Horror movies”, on

two Dr. Moreau movies: the 1933 Island of Lost Souls and the 1977 Island of Dr. Moreau. Both based on H. G. Wells’s 1896 novel.

Playful allusion. From my 2/1/19 posting “The natural history of snowclones”, about the playful exploitation of formulaic expressions, building on:

an idiom, cliché, striking quotation, proverb, saying, catchphrase, slogan, or [as in this case] memorable name or title

… this model [expression] may quickly extend by developing open slots, or by playful allusion. Sometimes, every part of the model that can be varied for effect is:

Eye Guy: Queer Eyes for the Spanish Guys, Straight guys for gay eyes, Homosapien eye for the Neanderthal guy

Brokeback: Backdoor Mounting, Breakdance Mountain, Brokeback Mounties

(Compare the plays on Waiting for Godot above.)

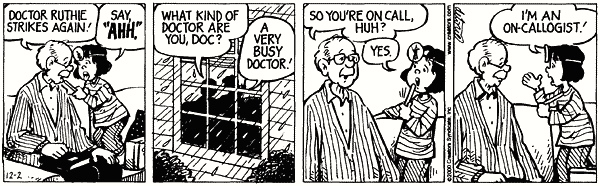

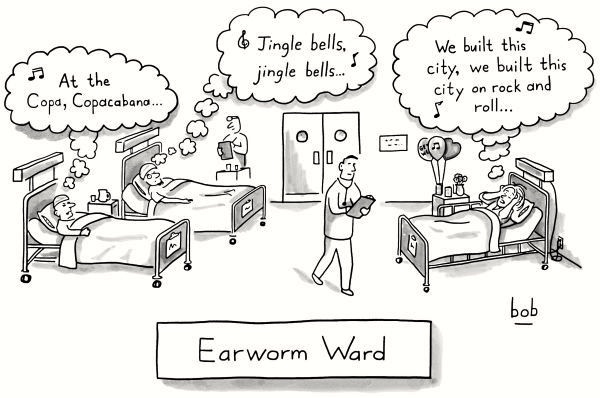

Title play: as a whole. There are many occasions and ways to wait. Waiting for Godot at the airport, in a Bizarro from 2/20/14:

![]()

(#3) (If you’re puzzled by the odd symbols in the cartoon — Dan Piraro says there are 2 in this strip — see this Page.)

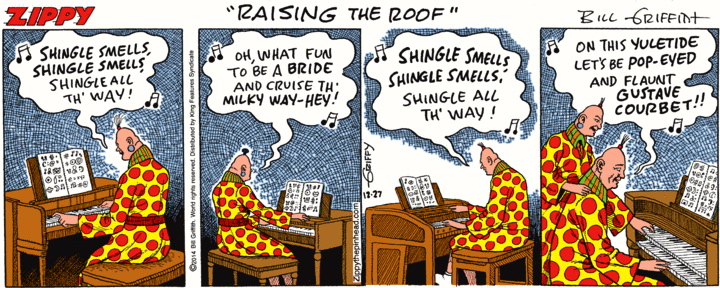

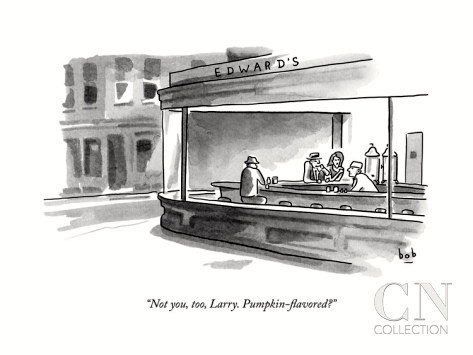

Wholesale parody. Now to the Open Culture site (“The best free cultural & educational media on the web”) on 5/18/15, with “Comics Inspired by Waiting For Godot, Featuring Tintin, Roz Chast, and Beavis & Butthead”. On the last:

I reserve my highest praise for the inspired casting of Beavis and Butthead in R. Sikoryak’s “Waiting to Go.” … Here we find a Vladimir and Estragon who truly embody the final lines of Norman Mailer’s notorious “A Public Notice on Waiting for Godot”:

Man’s nature, man’s dignity, is that he acts, lives, loves, and finally destroys himself seeking to penetrate the mystery of existence, and unless we partake in some way, as some part of this human exploration… then we are no more than the pimps of society and the betrayers of our Self.

The extraordinarily elaborate parody, with Beavis as Estragon and Butt-Head as Vladimir, and others to be introduced below:

![]()

(#4) B&B wait

Background on B&B, from Wikipedia:

![]()

(#5)

Beavis and Butt-Head is an American adult animated sitcom created by Mike Judge. The series originated from Frog Baseball, a 1992 short film by Judge originally aired on Liquid Television. After seeing the short, MTV signed Judge to develop the short into a full series. The series originally ran for seven seasons from March 8, 1993 to November 28, 1997. Fourteen years following the end of the series, the series was revived for an eighth season which aired from October 27 to December 29, 2011. A theatrical feature-length film based on the series titled Beavis and Butt-Head Do America was released in 1996 by Paramount Pictures.

The series centers on two socially incompetent teenage delinquents and couch potatoes named Beavis and Butt-Head (both voiced by Judge), who go to school at Highland High in Highland, Texas. They lack evident adult supervision at home and are dimwitted, undereducated and barely literate. Both lack any empathy or moral scruples, even regarding each other. They will usually deem things they encounter as “cool” if they are associated with heavy metal, violence, sex, destruction, or the macabre. While inexperienced with females, they both share an obsession with sex and tend to chuckle whenever they hear words or phrases that could even be interpreted as sexual or scatological.

Highlights from the Sikoryak. Panels 4 and 5 allude directly to the play:

Estragon: Charming spot. (He turns, advances to front, halts facing auditorium.) Inspiring prospects. (He turns to Vladimir.) Let’s go.

Vladimir: We can’t.

Estragon: Why not?

Vladimir: We’re waiting for Godot.

Then there’s the reference to death erection, again keeping close to the play (but enriched by the fact that in #4 this is an exchange between Beavis and Butt-Head, who revel in raunch):

Estragon: What about hanging ourselves?

Vladimir: Hmm. It’d give us an erection.

Estragon: (highly excited) An erection!

… Estragon: Let’s hang ourselves immediately!

[Digression on death erection. From Wikipedia:

A death erection, angel lust, or terminal erection is a post-mortem erection, technically a priapism, observed in the corpses of men who have been executed, particularly by hanging.

… Death by hanging, whether an execution or a suicide, has been observed to affect the genitals of both men and women. In women, the labia and clitoris may become engorged and there may be a discharge of blood from the vagina. In men, “a more or less complete state of erection of the penis, with discharge of urine, mucus or prostatic fluid is a frequent occurrence … present in one case in three.” Other causes of death may also result in these effects, including fatal gunshots to the head, damage to major blood vessels, and violent death by poisoning. A postmortem priapism is an indicator that death was likely swift and violent.

… In The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, art historian and critic Leo Steinberg notes that a number of Renaissance era artists depicted Jesus Christ after the crucifixion with a post-mortem erection. The artwork was suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church for several centuries. ]

At this point, two more characters — Pozzo and Lucky — appear. From Wikipedia:

Lucky is a character from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. He is a slave to the character Pozzo.

Lucky is unique in a play where most of the characters talk incessantly: he only utters two sentences, one of which is more than seven hundred words long (the monologue). Lucky suffers at the hands of Pozzo willingly and without hesitation. He is “tied” (a favourite theme in Godot) to Pozzo by a ridiculously long rope in the first act, and then a similarly ridiculous short rope in the second act. Both tie around his neck. When he is not serving Pozzo, he usually stands in one spot drooling, or sleeping if he stands there long enough. His props include a picnic basket, a coat, and a suitcase full of sand.

Finally, we get the “Shall we go?” dialogue (in a variant beginning “Should we go?”), as quoted from the play following #1 above.

Note from this morning, when I showed #4 to Kim Darnell, leading to this exchange:

KD: Well? Should you post?

AZ: Yes, I should post.

(He fails to post.)

That was 10 hours ago. Now I’m posting. I’m no longer willing — call me impatient, call me impetuous — to wait for Godot, Corot, Moreau (Dr. Moreau, or even Jeanne Moreau), Malraux, Perrault, or Poirot — or, of course, Waldo, Marlowe (the playwright or the private eye), Marlo (Thomas), Marlot (Kidder), Gordo, or any of that mofo lot.